The City of Cape Town’s drive to end load-shedding and move away from Eskom’s grid has received yet another boost, with the completion of its landfill gas wellfield and flaring system at Vissershok Landfill.

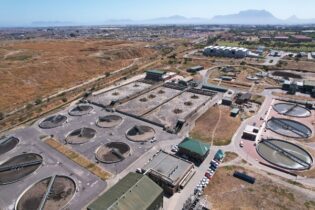

During June 2022, the City of Cape Town published a 10-point plan to end load-shedding in the city and move away from Eskom’s grid. The plan, which was addressed to President Cyril Ramaphosa, came as the country faced unprecedented bouts of blackouts. The City’s dual efforts to reduce emissions associated with landfill sites and reduce reliance on Eskom continued to gather momentum. The landfill gas wellfield and flaring system at Vissershok Landfill will begin operations soon to complement existing systems at the Coastal Park and Bellville landfills. The City is also making steady progress toward the generation of electricity from landfill gas. For the next three financial years, a total of R86.4 million has been budgeted for the operation and maintenance of the recently completed system at Vissershok. Furthermore, a system to convert landfill gas from this site into electricity is being designed for implementation around 2024/25, at an estimated cost of R197 million. Mitigating methane Alderman Grant Twigg, MMC for Urban Waste Management, City of Cape Town, explains that organic waste that decomposes inside a landfill is a significant contributor to climate change. “When organic waste breaks down in a landfill it produces landfill gas, which is a very potent greenhouse gas that contains methane. The incoming ban on organic waste being sent to landfill will help mitigate carbon emissions from landfills in future, but we also needed a solution to prevent emissions from organic waste that is already in the landfill,” says Twigg. “This is why the gas extraction and flare system will be put in place initially to burn off the gas before electricity generation equipment is installed. Production of electricity from this gas will also help reduce society’s reliance on fossil fuels, while reducing climate and health impacts.” The methane produced on landfills is known to have a global warming potential approximately 25 times greater than carbon dioxide. To reduce emissions from the landfill, wells are dug into the landfill site to extract the gas. These wells are then connected to the flare compound, where it will initially be combusted/flared, and in the future be diverted to a gas engine to generate electricity. Currently, the City is in the process of appointing a service provider to operate and maintain the recently constructed gas wellfield and flaring system at Vissershok. Furthermore, the gas turbine electricity generation system for this site has entered the design phase, with the first 2 MW generation infrastructure scheduled for implementation in 2024/25, increasing thereafter to between 7 MW to 9 MW of generation capacity by 2026/27, depending on gas yields.According to Eskom, 1 MW is enough to power around 650 average homes in South Africa, meaning that this system could potentially supply power for up to 5 850 average homes.

Carbon credits Like similar systems at the Coastal Park and Bellville South landfill facilities, the project has been designed in such a way that the City can earn carbon credits. A carbon credit is earned when an entity destroys one tonne of greenhouse gas that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere. The City of Cape Town Council recently resolved that these carbon credits would be auctioned off on the South African market to companies who need or want to offset their carbon emissions. Proceeds from the auction will be ring-fenced to fund urban waste management projects that reduce the health and pollution impacts of waste, and that will generate additional co-benefits such as job creation for communities. “At this stage, it is still too early to determine accurately how much greenhouse gas will be destroyed over the life of the project, or how much money the City will save by offsetting our reliance on Eskom, as it depends on gas yields that could vary over the 15-20 year lifespan of the project, depending on patterns of organic waste disposal in the City. “However, current estimates show that, between the sale of carbon credits and the expected reduction of bulk electricity purchases from Eskom, the project should pay for itself at least,” stresses Twigg. He adds that it is difficult to predict how much gas the landfill will produce; therefore, the project design has been formulated to allow for adaptation based on various scenarios we could experience over time. Even if electricity is not produced, the system will still earn carbon credits. “Although the expected contribution of waste-to-energy activities is not sufficient to reduce load-shedding on their own, the reduction in emissions is significant and will be achieved effectively at no additional cost to the ratepayer. Approximately 6 to 10 skilled or semi-skilled jobs (i.e. technicians) will be created in the operation and maintenance of the system. In addition, approximately 50 unskilled labourers are also required to assist with excavation during wellfield expansions.