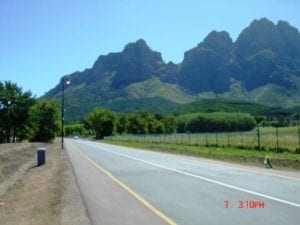

Pictured: A view of a section of the road before the project

Professional services firm SMEC recently delivered a project to the Western Cape Government (WCG), involving the rehabilitation and reconstruction of the Main Road (MR) 172 route – a scenic piece of road, which runs through the Winelands area towns of Johannesdal and Pniel towards Franschoek. The project, which won the 2011 SAICE Western Cape Award for Technical Excellence in Civil Engineering in the Community-Based Category and was announced as a national finalist for Consulting Engineers of Southern Africa (CESA) Engineering Excellence Awards in the R50-million to R250-million category, was unique in that it carefully balanced environmental and heritage sensitivities with numerous technical requirements. SMEC manager for roads and highways Western Cape Neil Slingers points out that road safety concerns which date back to 1999prompted the WCG to appoint SMEC (then VelaVKE Consulting Engineers) to undertake the planning and design for the upgrading and reconstruction of this section of the MR172. Slingers points out that what made this project unique is the area in which it was located: “The MR172 meanders through an area that is both environmentally sensitive and that is of national heritage significance. As a result, input and approvals were required from the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) and the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning (DEADP).” The existing road’s location and design elements were influenced by the topography, terrain, built environment, land use and historic significance of the neighbouring surrounds. Slingers points out that any future upgrades had to include these factors in the design. “Since inception, the project was an integrated one, whereby one part of the design could be done in isolation of any other factor. Hence the technical design could not be done in isolation of the environmental aspects, the heritage impacts and the social requirements,” explains Slingers. Public participation also played a key influential role in this project. “The communities of Johannesdal and Pniel were consulted as to their needs with regards to the MR172. It was vital to ensure that most, if not all, requests and desires were met. Once the conceptual design neared completion, SMEC prepared an innovative 3D-visualtion and presented it to all the stakeholders before finalising the design. This enabled stakeholders to better grasp the essence of the design and to visualise the end product,” Slingers points out. Initially the MR172 had a very narrow cross-section with a 6 m carriageway consisting of 3 m lanes and a gravel shoulder that carried approximately 4 500 vehicles per day. Preliminary design called for two 3,7 m lanes and two 2,5 surfaced roads to be constructed, however the intruding terrain and residential areas did not allow for the cross-section to be implemented. Instead, a compromise was reached whereby in the rural area two 3,7 m lanes and 1,5 m sidewalks were constructed.What’s more, it was decided that all accesses, both public and private, would be upgraded, which would add to the final quality of the product produced as some of the accesses were not of a suitable standard and would not have been in keeping with the upgrade of the road.

In addition to the onerous technical requirements, SMEC had to take into consideration limitations presented by the topography, the neighbouring residential area and high-traffic volumes during construction. “At no given time during construction could the MR172 be closed to traffic, which dictated that construction of road works and laying of pipes crossing the MR172 occur in half-widths. High volumes of traffic resulted in the contractor being limited to no more than three closures of 500 m long at least 1 km apart to ensure that the tail of preceding closure would not extend to the one behind it. Speaking on one of the project’s most significant challenges, Slingers says that the contractor and supervision team had to construct pavement layers through the town of Pniel by means of in-situ recycling. The road reserve was narrow and in many instances the existing houses, most of which were old and of heritage significance, were built on the reserve edge. “We therefore had to plan accordingly to ensure that all of the necessary precautions were in place in order to mitigate any damage to the structures as a result of the recycling,” explains Slingers. In order to facilitate movement of the community, sidewalks and walkways were constructed in Worcester Stone paving where space allowed, while all headwalls for pipes measuring 600 diameter and less were constructed from stone pitching instead of concrete to suit the aesthetics of the surrounding town and Winelands. Werfwalls were constructed at the start and end of the towns of Pniel and Johannesdal to demarcate the start of the residential area, while Cape Dutch style low walls were implemented around the church, which is seen as an integral area where the community converge. Importantly, the project was completed on the basis that as little of the existing vegetation be affected by the upgrade. “The road was realigned in the area stretching past Boschendal Wine Estate to preserve the trees and vegetation in this region and the unlined earth drain width was reduced in order to not affect the trees bordering the road,” explains Slingers. For traffic calming purposes and for aesthetics reasons, red shoulders were constructed to further enhance the design of the road. This is a first for the PGWP and has resulted in cyclists using the red shoulder instead of the main carriageway. In keeping with the vision of the project in terms of development, prior to going to tender and construction, an Economic Impact Assessment was carried out to identify how the surrounding communities of Pniel and Johannesdal could benefit from the project.