Mozambique’s coal rush is officially over and the government is now looking offshore to a gas bonanza, according to analysts at a coal conference this week in the capital Maputo.

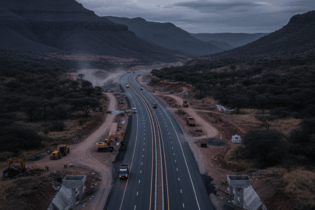

Just a few years ago, billions of dollars poured into Mozambique, one of the world’s poorest nations, in a twin scramble for inland coal and offshore gas. The gas rush is intact, but the coal boom has come apart at the seams, hobbled by low prices, overblown expectations, and a rail and port network that remains woefully inadequate. “At this stage Mozambique is not a coal story any more. It’s very expensive, very uncompetitive and they need a lot of added capacity,” said Thea Fourie, Africa economist at His, a financial and risk consultancy. “It’s really a liquefied natural gas (LNG) story now and I think the government is shifting its focus from coal to LNG,” she told Reuters on the sidelines of a Mozambique coal conference organised by Informa. In the coal region of northern Tete province, there has been a flurry of exploration permits issued and regular flights now connect this rural backwater to Johannesburg. But real action is limited. According to Andy Lloyd, an independent geological consultant, as of November 2014, 124 exploration licences had been issued in Tete. There are 11 approved mining concessions – the midway point to getting the green light to start a project. But only four operating licences exist and the companies involved are mostly stuck in for the long haul with deep pockets. One is Brazilian mining group Vale, which has a balance sheet that can allow it to hang tough for the long run in a country where it has linguistic and cultural ties formed from a shared Portuguese colonial past.Another, International Coal Ventures Private Limited (ICVL), is an Indian company which wants to expand the Benga mine it acquired from Rio Tinto in a fire sale after the global mining giant pulled the plug on its ill-fated foray into Mozambique that included a write-down of $3.5 billion.

ICVL was set up by the Indian government to acquire and develop coal assets to meet the needs of state-owned firms such as the Steel Authority of India, and so the company has potentially deep sources of finance it can tap. Other projects are not going to get any coal out of the ground any time soon in Mozambique. “Work here is likely to come from the companies that have their equity investments at the moment. Financing sources are going to remain difficult to tap until the commodity prices have recovered,” said Chris de Vries, Johannesburg-based mining advisor at VenmynDeloitte. Pulling the stuff out of the earth is also not viable if it can’t be moved. Mozambique only has rail capacity for about 6 million tonnes of coal a year. China, by way of contrast, can do a billion. Mozambique’s infrastructure woes have been thrown into sharp relief by the collapse last week of a coal stacker at the port of Nacala, dealing a blow to Vale’s efforts to start coal shipments from the African nation this year. Offshore, the LNG space in Mozambique remains a world of deals and big money. Africa-focused Standard Bank expects the LNG deals to swell the state purse of Mozambique. It sees an Anadarko project adding $67 billion to government revenue over its 30-year life, rising to $212 billion once the two initial plants are expanded to six. – Reuters