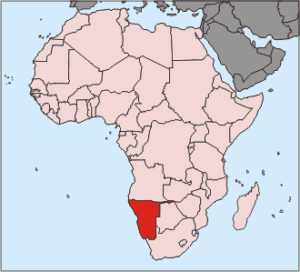

The Walvis Bay Corridor Group (WBCG) , a private-public partnership (PPP) established in 2000, is on a mission to make Namibia the new gateway into the SADC region as Tristan Wiggill finds out.

The WBCG group consists of the Namibian Transport Association, Air Namibia, the ministries of Finance, Home Affairs, Trade and Industry, and Works and Transport, the Roads Authority, Container Liner Operators Forum, the Namibian Logistics Association, the Chamber of Commerce, Port Users Association and the largest stakeholder, Namport, which runs the port of Walvis Bay. Namport CEO Bisey Uirab is chairman of the WBCG board. Associated members are based in South Africa, Zambia, the DRC and Brazil and there are associate freight forwarders and transporters, as well as companies and individuals wanting to increase their knowledge of SADC. Focus areas include Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Southern DRC, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Botswana and South Africa. Forming a PPP was a challenge for the WBCG, as it had to be started from scratch, without any precedents to compare itself to. Neighbouring countries weren’t too excited about the PPP and the world had limited knowledge of Namibia and what it could offer. Few knew what its infrastructure was capable of or what solutions it could offer and it took 15 years to convince the shipping lines to buy into the concept. The WBCG first registered as a section 21 company and then focused on the corridors. It started by looking at landlocked countries to see how it could better serve them as an alternative – not to take business away from South Africa, but to be an alternative solution. In so doing, it became, in a sense, a marketing arm of the Namibian government. Masterplan In 1990, the WBCG started with its first transport masterplan, which stated that it wanted road linkages to its neighbours as well as the creation of road, rail, air and port institutions. By 2000, it had formalised its sector by creating awareness. It started travelling to different countries, not just within Africa, but also abroad in a campaign to educate people on what its vision and dreams were, explaining the attraction of Walvis Bay. It extended its rail line to Angola’s border, which was the best move it could’ve made as a lot of coal had to be railed into that country. It formed partnerships with its neighbours and concluded memorandums of agreements. It then initiated the secretariats on the two transport corridors. The WBCG had to create market presence, ensure good service delivery and learn the business culture. It had to formalise Namibia as a unified group, which is why the PPP was so important. It had the ports, the customers, the rail and the logistics but everybody needed to sit around a table and work collectively. The WBCG’s core service is development, with a development manager responsible for South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe. There are regional offices, too, to help the WBCG understand the cultures, business ethics and process flow within different states. A core focus is trade facilitation and infrastructure development, and the WBCG works closely with the Namibian government in terms of ports, roads and rail development. Logistics hub The WBCG wants Walvis Bay to be seen as a logistics hub for Southern Africa and the Namibian government has invested a lot of funds into promoting Walvis Bay as a gateway into SADC, expanding the Walvis Bay port and linking its corridors to Angola, the DRC, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Malawi and South Africa. Its vision is to be ‘the’ gateway port into SADC. The group has common PPP objectives where everybody agrees on the vision. Decisions are made collectively; one person does not head up the whole initiative. The WBCG has the passion and the desire to create the logistics hub and gateway ports into Africa. The PPP has been exceptionally successful in terms of collectively deciding on a strategy, putting it in place, implementing it and measuring it. Its first initiative was to develop the Walvis Bay port, which it started in 2014 and which should be complete by end 2017, at which point it’ll be able to handle 1 000 000 TEUs per annum. In 2000, this figure stood at 20 000 TEUs, growing to 377 000 by 2012 and is, at the moment, in excess of 700 000 TEUs. The new container terminal was funded by the Namibian government at a cost of Nam $3 billion as the land had to be reclaimed and dredged quite a bit. The upgraded port will also be able to receive passenger vessels, with MSC cruisers and the like able to start calling on Walvis Bay. Much transformation has occurred within the WBCG since it started out as a transport corridor. It wants to create the best trade route to Southern Africa and has formed strategic partnerships with several neighbouring countries, with relevant associations and with governments surrounding Namibia. Understanding According to a memorandum of understanding signed two years ago between Botswana and Namibia, the WBCG is expecting about 60 million tonnes of coal to run on the Trans-Kalahari rail line. The feasibility study has been completed but the WBCG needs private and public partners to fund what is likely to take about 20 years to establish. About 250 km of rail needs to be built to link up with Zambian rail, which will then facilitate the DRC. Angola is far ahead, though, having already implemented its rail line, and it’s a challenge for the WBCG – in terms of the copper belt – to keep volumes through Walvis Bay. Angola has always been Namibia’s cargo rival and, since it has improved its infrastructure and services, has been able to secure quite a lot of the available cargo in recent times. Namibia’s rail infrastructure was built in 1906 and a number of lines have been refurbished since then. The country has refurbished the line going up to the Angolan border, but now the second project is to link the line to Zambia. These governments are investing their own money to ensure that rail infrastructure is on par with other landlocked countries. The Botswana line will be developed once coal is mined and the quality of the coal has yet to be determined. The WBCG also has to increase logistics capacity, with companies from outside Namibia encouraged to establish a logistics hub within Namibia to serve increased volumes. Location, location, location

The WBCG has to optimise its location because West Africa offers shorter sailing times from the Americas, Europe and the Far East. All major shipping lines call directly on the port of Walvis Bay, which is no longer seen as a transhipment hub or fishing port.

In fact, transport and logistics have increased in terms of Namibia’s GDP contribution.

• 3 to 4 days to Zambia or Zimbabwe

• 3 to 5 days to Angola

• 5 to 6 days to the DRC or Malawi In instances of congestion, whoever runs the committee on the secretariat with the affected corridor is called to sort it out. They physically go there and sort out the issues. Challenges There’s a huge problem with HIV in rural areas on all the corridors. As this results in a high mortality rate with truck drivers, the government has funded a large team to assist with this problem. In an attempt to raise awareness of this problem, the WBCG’s CEO took part in an HIV test in one of the mini-vans. Capacity is also an ongoing challenge; there are only 2.4 million people living in Namibia and the country is made predominantly of deserts, thus land is exceptionally expensive. Even so, regional growth really started in 2005 when the WBCG opened an office in Zambia, followed by Johannesburg in 2008 and, more recently, in Lubumbashi, DRC and Sao Paolo, Brazil. It will soon open an office in the Netherlands because it is finding a lot more volume coming from Europe and, so, it is necessary to have representation there. Brazil is important; the WBCG wants to export everything and the linkage between port Santos and Walvis Bay equates to seven days sailing time. One could get products to South Africa within 10 days, Zambia within 15 days and the DRC within 17 days. The Brazil office is based in Sao Paolo, which is close to Port Santos. Brazil has an Intermodal show every year. This year, 48 000 visitors attended. Brazil is an energised country that wants to attract business. In March, the government put aside $500 000 to substitute travelling expenses for companies willing to invest in and import from Brazil. The WBCG is trying to create, or rather re-establish, the route between Brazil and Walvis Bay. In 2012, it formed its new transport master plan, which was more like a logistics master plan, and began attracting investments and interest from Europe, America and South Africa. The latter opened up its own hubs within Walvis Bay, which included everything from clearing and forwarding to warehousing, to cross-docking to transport – in other words, everything comprising the supply chain. The WBCG strategises how to grow Namibia’s economy and attract volumes to the port. It has looked at its port costs, renegotiated on different parts of the supply chain and cut fat to attract business. It tries to implement new routes and rates and receives different types of vessels. Bridging the gaps The widening of the Katima Mulilo bridge, which links Namibia to Zambia, was a WBCG initiative. It has also assisted with infrastructure development in several other locations, in order to handle abnormal cargo going over into Zambia – often to the copper belt – which makes a handsome contribution in terms of volumes and subsequent revenue. The WBCG’s project focus has always been on long-term strategies that benefit regional, international and national clients and it does a lot of marketing overseas. It frequently travels to the Far East, Europe and the Americas to market the country to big players looking to invest in Africa. Many of these companies want to export into Africa and it’s the job of the WBCG to create a different, alternative route into the continent. The availability of truckers has also been an issue for the WBCG and that’s why it has attracted blue chip companies. Road transport is the WBCG’s main source of revenue and so it needs trucks, not just from South Africa, but also from abroad. It also needs foreign companies to open up logistics hubs within the country to serve the logistics market in terms of trucks and transport. It provided new routes because there was only one route historically, and that was through South Africa. South Africa and Namibia had a lot of cross-border issues in terms of permits. It was a challenge to get trucks through customs, but the WBCG managed to eliminate many of those issues by spending time on each side of the border. If you’re sitting in South Africa and looking at importing cargo, the first question people ask is ‘Why am I going to bring it through Walvis Bay instead of Durban?’ Durban is 600 km away; Walvis Bay is over 2 000 km away. The answer depends on what one’s core need is – time or cost? Basil Reed moved every component it needed to build the St. Helena airport on the Trans-Kalahari corridor through Walvis Bay, with the WBCG meeting its KPIs 99%. Apart from an incident involving a Zambian syndicate several months ago, no loads have been compromised and there are minimal issues with bribery, corruption and hijackings. There’s definitely an opportunity for growth. In 2007, Namibia processed only 2.2 million tonnes of cargo and was able to double that in two years. Daily truckloads between Botswana, Zambia and Namibia grew from 182 to 377. By 2025, Namibia aims to be the new Dubai for Southern Africa, but it will need its logistics hub to be established and working efficiently by then. The WBCG’s biggest hurdle is doing more with less. In order for it to succeed, it has to look hard at its customers to understand what they need and then put appropriate solutions together for them from start to finish.