Africa is drawing from its own lessons as it works toward land degradation neutrality (LDN), with the Southern African Development Community (SADC) adopting its own Great Green Wall Initiative (GGWI) strategy based on the continent’s experience in the Sahel.

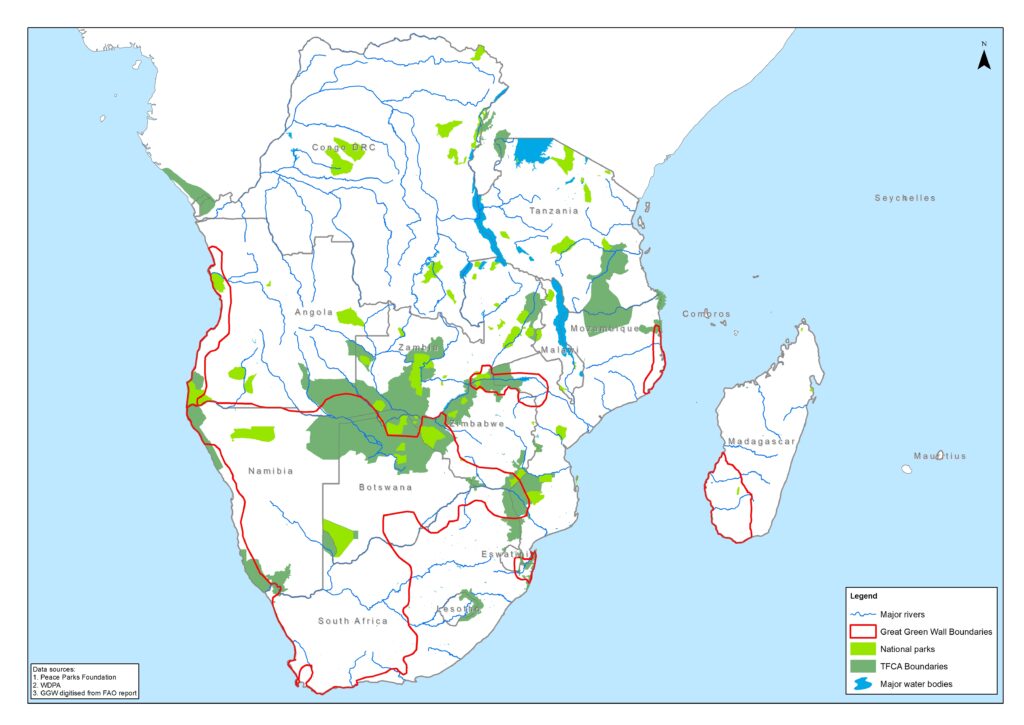

The underlying goal is to combat desertification and mitigate the effects of drought in countries experiencing serious land degradation. The original GGWI has for the past 15 years been implemented in Africa’s Sahel region. The Sahel is a semi-arid zone between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. This large area includes parts of Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia. The Sahel’s GGW is an ambitious project that works toward not only halting land degradation but bringing life back to vast swathes of land on the Sahara desert’s southern edge – which is one of the poorest regions of the planet. The vision is to create an 8,000 km ‘natural wonder’ across the width of Africa. This, it is hoped, will be pivotal in improving food security, employment and general social stability. This vision has inspired the SADC region, according to Darryll Kilian, partner and principal environmental consultant at SRK Consulting. Kilian notes that southern African countries face many similar land degradation trends and risks, and are keen to apply the lessons learnt in the north. “As part of their commitment to reversing land degradation – as well as planning for the impacts of climate change – SADC member states in 2019 adopted the SADC Water-Energy-Food (WEF) Nexus Framework,” said Kilian. “This draws on the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RSIDP) and other sectoral policies to develop better alignment in WEF polices, strategies and programmes.” Working with the secretariat of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), SADC has begun leveraging the lessons from the Sahel GGWI. This has begun with the SADC Secretariat and its member states drawing up a regional approach for a GGWI for Southern Africa. “This initiative hopes to combat land degradation by building on existing land-based initiatives and programmes to advance socio-economic development and promote environmental sustainability,” he said. He recently led an SRK team in conducting a Global Land Outlook for Southern Africa, on behalf of the UNCCD and in cooperation with the SADC Secretariat. The study highlighted the value of many case studies – including the GGW – in demonstrating how the nexus between land, water and energy can be leveraged to make development change more effective. “The restoration potential of the GGWI for Southern Africa includes a land area of some 228 million hectares of dry and degraded land,” he said. “Among the aims of the initiative is to reduce ecosystem vulnerability and climate change impact, as well as increase the resilience of communities to climate change factors.”

“It is helpful to reflect on the key challenges and lessons in implementing the GGW in the Sahel region to inform the SADC region in its way forward,” said Kilian. “There are some regional similarities, which include increased population growth, conflict over natural resources, unsustainable agricultural practices and lack of sustained finance.”

At the same time, there are challenges that reflect the differences between the regions. For example, the countries of the Sahel region display political and cultural diversity – but from a biophysical perspective there is general uniformity in terms of an arid landscape with little land carrying capacity. “Southern Africa, on the other hand, displays a diverse mix of landscapes – from tropical rainforests in the DRC to deserts in Namibia,” he said. “Nonetheless, by adopting lessons learned, the GGWI for Southern Africa can overcome and manage many of the anticipated challenges.” Among the lessons is the need to adopt interlinked initiatives and activities, where projects focus on achieving multiple benefits for a range of stakeholders at different scales, he emphasised. “Attention also needs to be paid to capacity building through data collection and knowledge sharing, to utilise the most appropriate restoration approaches and to create public-private partnerships that can operate effectively,” he said. “Building on local knowledge systems will be vital for scaling up results on the ground.” This can be achieved by implementing traditional or indigenous farming techniques in large-scale restoration projects, as seen in the Sahel. For example, Zai pits were used in Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso to maximise the capture of rainwater, reduce run-off and increase infiltration and soil fertility.