By 2030, South Africa will generate an estimated 750,000 tonnes of electronic waste (e-waste) each year, a staggering figure for a country still struggling to divert even a fraction of its refuse from landfill.

Despite a national ban on the disposal of e-waste, between 90 and 95% of the material never reaches recycling facilities. Instead, obsolete electronics are stockpiled, or dumped, trapped in the grey zone between ownership and disposal. This disconnect between policy and practice is the focus of a conference paper by Mark Williams-Wynn and Marcin Durski of EWaste Africa. Their work highlights a sobering truth: South Africa’s challenge is no longer technical feasibility; it is about accessibility, motivation, and behaviour. Even with the right laws in place, e-waste continues to slip through the cracks because recycling remains inconvenient, undervalued, and misunderstood.The invisible hazard in our homes

E-waste is often difficult to recycle due to its use of many different materials, requiring manual disassembly

Why good policy has not changed bad habits

E-waste is unique among waste streams because it straddles the line between resource and liability. Many consumers cling to outdated electronics because they appear valuable, even when they no longer function. For wealthier households, old devices are often passed down rather than discarded as a gesture of goodwill that, unintentionally, transfers environmental risk to poorer communities lacking access to recycling infrastructure. In peri-urban and informal settlements, discarded electronics are frequently mixed with general waste or burned for metal recovery. The informal recycling sector plays a vital role in resource recovery but often under unsafe conditions. Some reclaimers go as far as to dismantle circuit boards by hand, burn wires in open air, and use acid baths to extract metals, releasing toxins into soil and water. The study identifies four interlinked barriers to effective diversion:- Inadequate infrastructure, patchy recycling networks, and limited drop-off sites.

- Weak enforcement and fragmented policy.

- Behavioural and socio-economic barriers, from apathy to misperceived value.

- Low public awareness about recycling options and environmental risks.

Recycling must be as easy as throwing away

Many South Africans keep or give their e-waste away, but as collection points becoming more common so does e-waste recycling

“We must make e-waste drop-off as convenient and routine as buying bread or petrol,” they argue. This insight is grounded in behavioural research showing that convenience is the single biggest predictor of recycling participation.To that end, collection infrastructure must evolve from sporadic pilot projects to permanent, visible, and user-friendly systems. Examples include:

- Public drop-off points at libraries, police stations, or shopping centres.

- Community collection hubs in townhouse complexes or gated estates.

- Mobile collection days for rural or peri-urban areas, paired with awareness campaigns.

Integrating the informal economy

South Africa’s informal reclaimers are already embedded in the recycling ecosystem. Rather than excluding them, reformers argue for structured integration providing safety training, fair pricing, and formal market access.Currently, reclaimers often sell e-waste to unscrupulous scrap dealers who pay cash with no environmental oversight. Formal recyclers, by contrast, offer lower payouts but higher compliance standards. Bridging this gap requires innovative incentives, supported by Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) funds or municipal partnerships, that reward environmentally sound recovery without penalising informal livelihoods.

Such integration can transform e-waste collection from a survival activity into a green micro-enterprise sector, aligning environmental outcomes with economic inclusion.Policy coherence and producer accountability

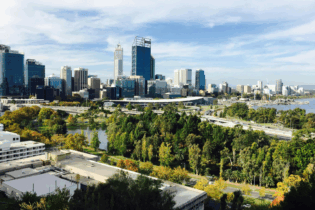

By 2030, South Africa will generate an estimated 750,000 tonnes of electronic waste

- Stronger alignment between the National Waste Management Strategy (NWMS 2020) and municipal delivery plans.

- EPR enforcement through transparent registration and traceability, including labelling requirements for second-hand and refurbished devices.

- Cross-agency collaboration between the DFFE, SARS, customs, and law enforcement to curb illegal imports and unregistered producers.

Behavioural insight, recycling is personal

Legislation and infrastructure can only go so far. The final frontier is human behaviour. Research across South Africa shows that many households fail to recycle not because they reject the idea, but because they lack information, motivation, or feedback. The paper highlights five behavioural interventions to close this gap:- Promote civic responsibility, frame e-waste disposal as a moral obligation.

- Offer small, tangible incentives, from mobile data to product rebates.

- Recast informal collectors as community recyclers, not nuisances.

- Challenge fatalism, counter the “my effort doesn’t matter” mindset.

- Celebrate success, publish feedback on diversion rates to build shared pride.

Education and visibility, the missing links

Many South Africans simply do not know where or how to recycle electronics. Awareness campaigns, if they exist, are often short-lived or poorly targeted. A sustainable communication strategy should:- Provide clear, consistent information on what can be recycled and where.

- Use multiple languages and visual cues to reach diverse audiences.

- Leverage schools as long-term incubators of environmental responsibility.

From stockpiles to circularity

Ultimately, South Africa’s e-waste problem is not one of ignorance, but of inertia. The system requires practical pathways that translate regulation into action, pathways that connect the citizen at home to the recycler at the end of the chain. The way forward is clear:- Build accessible infrastructure, everywhere, not just in affluent areas.

- Integrate the informal sector, safely and sustainably.

- Enforce EPR compliance, closing loopholes that reward inaction.

- Embed behavioural and educational strategies that make recycling a social norm.

Dr Mark Williams-Wynn, chief technical officer of EWaste Africa

Dr Marcin Hubert Durski, research and development manager at EWaste Africa