Despite the lack of formal statistics on available landfill space, those in the waste management industry agree that it is rapidly filling up – and that the country is on the verge of a crisis.

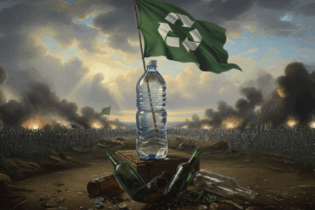

“We had pretty well-run facilities around the year 2000, but our landfill sites are currently in a terrible state; the worst they’ve been in decades,” warns Leon Grobbelaar, past president of the Institute of Waste Management of Southern Africa (IWMSA). “Until South Africa has a formal policy to ‘reduce, reuse and recycle’, we will continue to fill up our landfill space at this frightening rate.”According to Grobbelaar, the problem is very complicated with various contributing elements – despite legislation. He points out that South Africa has some of the best waste management legislation in the world. “We incorporated knowledge from other successful countries into our legal framework, which took the form of the local National Environmental Management Waste Act (NEMWA),” Grobbelaar said.

The issue is that this legislation is not being enforced. he explained that “the South African Waste Information System, or SAWIS, is one example. Users are supposed to submit reports on the tonnages of waste generated, recycled, and disposed of to that system, but they don’t because they know there are no repercussions.”

Grobbelaar further stated that a lack of future planning will soon be one of the major concerns that towns and cities will have to deal with. “They are responsible for providing services for citizens to dispose of their waste,” he says. “Thus, they are obligated to develop additional landfills. However, municipalities in South Africa simply do not have the means or capacity to do so.”

The last time the cities of Johannesburg and Tshwane licensed or constructed a new landfill was in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, Grobbelaar says, and now they are filling up at an alarming rate.

“However, the licensing and construction process for a new landfill typically takes three to five years, followed by appeals and possible legal processes. So, even if our major cities opted to start this process tomorrow, we won’t have new facilities until approximately 2030.”

Though the problem may feel overwhelming, individual actions can make a difference.

“First and foremost, we should all be very conscious of what we put in our ‘black waste bag’,” Grobbelaar says. “We should have a two-bag system, with one for dry items and the other for wet materials.”

Glass, tin, paper, and plastic (recyclables) are among the items that should be put out for our informal waste pickers – the so-called “Trolley Brigade” – to recover. “The second bag should be for ‘wet waste’. This includes the waste we generate in the kitchen such as fruits, vegetable peels, and leftovers. It has the potential to contaminate dry waste and has no real market value.”

Grobbelaar urges consumers to also ensure they don’t mix garden greens with domestic waste, as garden greens can be shredded and composted. “If you are unsure of where you can dispose of your recyclables, garden greens or builders rubble waste, you can contact the IWMSA who will gladly assist and point you in the right direction,” he says.