The recent Institute of Retirement Funds Africa (IRFA) conference raised important discussions about the extent to which South African retirement funds are investing in infrastructure projects. While the retirement fund industry acknowledges the critical need to support the expansion and upgrading of infrastructure – including transportation, energy, water and sanitation, etc.- South Africa’s retirement funds hold substantial capital that could potentially meet these demands. Yet, we are not seeing a rush of funding directed towards infrastructure investments. Why is this the case?

Before addressing this question, it’s essential to first examine whether there are genuine, viable infrastructure investment opportunities in South Africa that align with the investment objectives of retirement funds.Infrastructure pipeline

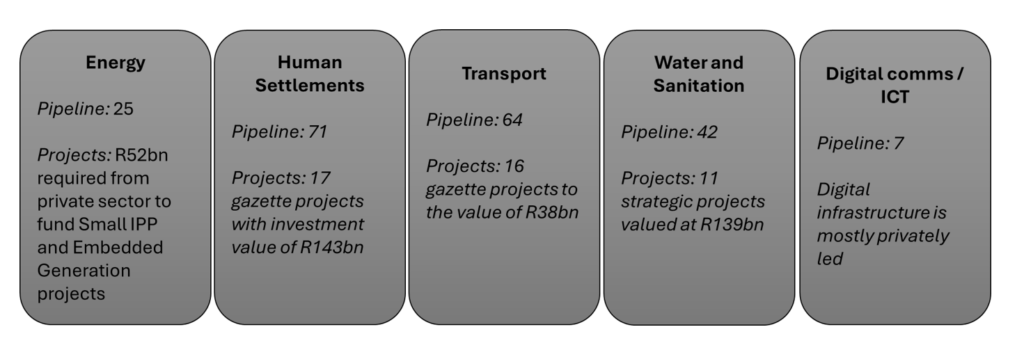

There are a significant number of local projects that require funding. Included in the figure below is an overview of the number and Rand value of these projects – separated by sector. It is difficult to know exactly what proportion is investable (“bankable”) for a retirement fund, but engagements with the industry suggests this number to be about 20%. Assuming the 20% proportion, that means that there is a funding need of between R75bn and R100bn. If a higher proportion is bankable, then the investment need increases.Infrastructure investment plan per sector

www.infrastructuresa.org, Momentum Investments, 2024

- Regulatory conflict

- Lack of alignment and consistency

- Infrastructure specific factors.

1. Regulatory conflict

South Africa’s legislative framework often experiences conflicts and a lack of alignment between different pieces of legislation. This can complicate governance and regulatory processes. Here are some key points regarding the conflicts between national and provincial legislation:- Constitutional framework: The South African Constitution provides a mechanism for resolving conflicts between national and provincial legislation. According to Section 146, national legislation prevails over provincial legislation if it aims to maintain uniformity across the country or addresses issues that cannot be effectively managed by provinces individually.

- Environmental legislation conflicts: Specific conflicts arise in areas like environmental legislation, where national and provincial laws may differ. This can lead to confusion regarding compliance and enforcement, as stakeholders must navigate potentially contradictory regulations.

2. Lack of alignment and consistency

- Contradictory legislation: Various pieces of legislation, such as the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA) and the Municipal Systems Act (MSA), sometimes contain contradictory requirements. For instance, both acts mandate feasibility studies before forming public-private partnerships (PPPs), but they prescribe different time frames for these studies—approximately two years under the MSA and six months under the PFMA. This inconsistency can lead to varied interpretations and implementations of the laws.

- Implementation challenges: The lack of functional mechanisms to ensure that robust PPP legislation is properly interpreted and implemented contributes to the inconsistency. There is often a gap between legislation and its practical application, leading to a variety of partnerships that may not conform strictly to legal requirements.

- Accountability issues: There are also concerns regarding accountability and oversight in the implementation of PPPs. The absence of external auditing and limited public consultation can exacerbate the challenges posed by conflicting legislation, making it difficult to ensure compliance and transparency.

3. Infrastructure specific

There is a notable conflict between legislation governing pension funds and infrastructure investment in South Africa, primarily due to the complexities surrounding Regulation 28 of the Pension Funds Act and its implications for infrastructure investments. The key points of conflict are:- Investment limits: The January 2023 amendments to Regulation 28 allow retirement funds to invest up to 45% of their assets in infrastructure projects. While this is a significant increase aimed at promoting infrastructure investment, it also places the onus on trustees to ensure that these investments align with their funds’ objectives and risk profiles. The regulation aims to protect members from excessive concentration in illiquid assets, which can create tension between the desire for higher returns through infrastructure and the need for liquidity and risk management.

- Definition of infrastructure: The definition of “infrastructure” has evolved through the amendments but still poses challenges. Initially, the definition was limited to projects within the National Infrastructure Plan, excluding private sector and offshore investments. The updated definition now encompasses a broader range of assets, but the complexity of identifying suitable infrastructure projects that meet regulatory criteria remains a challenge for asset managers.

- Administrative burdens: The new regulations introduce additional reporting requirements for pension funds regarding their infrastructure investments. This includes classifying all infrastructure investments and ensuring compliance with the new definitions. The increased administrative burden can deter pension funds from engaging in infrastructure investments, as they may lack the necessary expertise or resources to navigate the complexities of these new requirements.

- Risk management concerns: Infrastructure investments often come with significant risks, including project delays, cost overruns, and regulatory changes. Trustees are required to balance the potential for stable, long-term returns against the inherent risks of infrastructure projects. This balancing act can lead to hesitancy in committing to infrastructure investments, particularly if the regulatory framework does not provide adequate guidance on risk assessment and management.

- Structure of Trustee meetings and decision-making: Most fund trustee boards or investment committees meet quarterly. When asset managers source funding, the decision-making processes of trustees is lengthy. Frequently, by the time the decision is made, the required funding has been sourced elsewhere, or the opportunity has dissipated. This can be resolved by funds investing into multi-managed / fund-of-funds structures or products, but it needs to fit into the operating methodology and philosophy of the fund.

- Complexity of investing in private markets: Infrastructure investments are far more complex for trustees to understand than listed investments such as equities and bonds that trustees are familiar with. There are not only investment matters that need to be understood, but also complex legal matters relating to partnerships and private equity-type structures. Infrastructure investments will also frequently experience a “J” curve, and trustees grapple with the fairness of members experiencing the initial decline of the “J” and not necessarily experiencing the growth thereafter due to their retirement or withdrawing from the fund. The lifestage structure addresses some of these concerns – such as only investing accumulation phase portfolio assets into illiquid infrastructure. However, the existence of savings and retirement pots under the two-pot system creates further complexity. It will be challenging to invest illiquid investments in the savings pot. To prevent this from happening, one therefore needs different investment strategies between the retirement pot (where illiquid investments belong) and savings pots (where illiquid investments could be problematic). This is a complex matter. The above can lead to trustees not having the appetite to pursue such investments.

Summary and possible way forward

Evidence and experience indicate that the retirement fund industry is not lacking in interest when it comes to investing in infrastructure. However, the reality is that these investments are challenging to source, package, and even more difficult for trustees to commit to. By nature, infrastructure investments are complex, and many trustees feel underprepared to commit their funds and members to these long-term investments.

Rob Southey, Momentum Consultant and Actuaries