Garreth Russel, MD of RevoWaste

Problem plastics

Not all plastic is created equal, recycling plastic begins with sorting and some plastics are skipped over entirely, something Russel wants the industry to overcome

“The fumes released when you extrude flame-retardant plastics are toxic,” Russell said. “We use activated carbon filters and water baths to capture emissions, so we can pelletise them safely.”Plastic strapping, widely used in packaging, caused a different headache. “If you put it through a normal granulator, it just wraps around the blades and melts. We worked with Circular Energy to design a custom-built system. One customer alone produces 30 tonnes a month, material that used to be thrown away.” Even PET has untapped challenges. While bottle-grade PET is widely recycled, thermoform PET, used in cake trays and disposable cups, is not. “Locally, there’s no demand for that grade. The volumes are staggering, yet they’re simply thrown away. We’ve found export routes to India and Brazil where it’s wanted.”

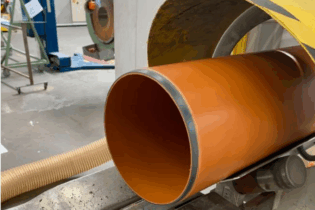

Polystyrene: from air to ingots

Melted and compressed polystyrene, this enables the transportation and recycling of a very light product that proves difficult logistically

“The biggest challenge is not that it can’t be recycled, it’s that it’s so light,” said Russell. “A truck that could carry 30 tonnes only collects 100 kilos of polystyrene. The economics don’t work, and the carbon footprint goes through the roof.”Revowaste invested in a machine that shreds, melts and compresses polystyrene into dense ingots. “You go from transporting air to transporting 30 tonnes of usable material. Companies like Supreme Mouldings then remanufacture it into skirting boards and decorative wall panels.” The company is now exploring how to handle food-grade polystyrene containers, which are contaminated with oils. “Those oils are flammable during extrusion. We’re developing a wash process that separates and recovers the oils, so the material can be safely recycled.” Russell is equally concerned about protecting workers. Shredding and granulating plastics creates microplastics invisible to the eye. “We don’t want our operators breathing them eight hours a day,” he said. “We issue respirators and ensure all processing happens indoors, in industrial zones, away from food or residential areas. Responsibility doesn’t stop at recycling ,it extends to how we do it.” While overseas recyclers increasingly rely on automated camera-based sorting, Russell insists the South African context calls for a human-centred approach. “They cost millions, and the margins here are too tight. Even if we could afford them, I’d rather employ people than buy a machine that will be obsolete in two years. Our staff are loyal, and we’re loyal to them.” Margins in plastic recycling remain slim,. Revowaste has responded by scaling volumes and planning to manufacture finished products.

RevoWaste prioritise staff training and rely on labour, rather than machines which are expensive and displace employment opportunities in South Africa

“EPR has been nothing but beneficial,” said Russell. “It’s given us access to more waste and provided subsidies for collection. The partnership with Reclite is unique; even our international visitors find it unusual. By working together, both companies expand what they can offer customers.”For Russell, collaboration is as important as competition. “Everyone wants to hide their ideas, but that doesn’t do anyone any favours. The industry is big enough for all of us if we share knowledge and experiences.” “Plastics are the toughest challenge,” Russell said. “But with the right approach, they can be turned from a global problem into a valuable resource. For me, it’s about more than running a business; it’s about helping to clean up the planet.”