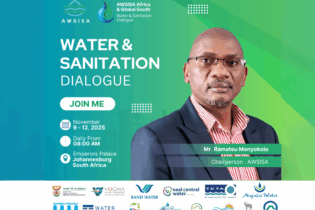

Ramateu Monyokolo, chairperson of both Rand Water and AWSISA

“In the past, when individual water boards approached government about issues such as municipal debt, we had very little impact. But through AWSISA’s unified platform, we successfully lobbied National Treasury to withhold equitable share transfers to 18 defaulting municipalities – a first in South Africa’s history.”

Debt

Stable governance is essential for ensuring water security, as the success of bulk water provision is premised on capable and credible accounting authorities, specifically boards of directors

SPVs

The collapse of municipalities leads to the collapse of boards

“We have successfully built and maintained water treatment plants, reservoirs and booster stations and can assist municipalities in strengthening their own water infrastructure. Water boards have the balance sheets to attract funding and have the technical expertise, institutional capacity, and operational experience to help professionalise and capacitate the rest of the water value chain. Public-public partnerships between water boards and municipalities is a great solution.”Public-public partnerships between waterboards and municipalities have already occurred via Section 63 of the Water Act. This is where the Minister of Water and Sanitation assigns responsibility for water service provision (wholly or partly) to another competent organisation (such as a water board) when there’s a breakdown in service delivery. Section 63 provides a funded mandate, ensuring that financial resources accompany the transfer of responsibility for service delivery. This mechanism has been applied at Emfuleni Local Municipality, where Rand Water was appointed to address sewage pollution and upgrade wastewater treatment works, and at uThukela District Municipality, where uMngeni-uThukela Water was tasked with managing and maintaining water and sanitation infrastructure. According to Monyokolo, Section 63 is a short term intervention as Treasury has limited budget. “It is effective, but it is not a permanent solution. The introduction of SPVs will eliminate the need for Section 63 interventions.” With an SPV, the operations, assets, revenue and grants relating to the water and sanitation division of a municipality would be ring-fenced. Rand Water is piloting the country’s first SPV with the Emfuleni Local Municipality. Approved by both the Minister of Water and Sanitation in November 2024 and National Treasury in June 2025, the initiative aims to ring-fence water and sanitation revenues, professionalise operations, and attract private financing for infrastructure upgrades. A process is underway to appoint an interim board and the SPV is likely to be launched in December. Monyokolo says such models will help tackle non-revenue water, which now averages around 49% nationally. “In Gauteng, even though Rand Water has increased capacity to 5.6 billion litres a day, half that water is lost through leaks, theft and poor maintenance. The more water we pump into the system, the more water we lose through leaks.” Leaks occur for several reasons — some stem from neglected maintenance of reservoirs, pipelines, valves and meters, while others result from theft and vandalism. In certain cases, individuals illegally tap into pipelines to steal water, while the so-called ‘water mafia’ deliberately damages infrastructure to secure repair or water tanker contracts.

Informal encroachments

Illegal water use is often associated with informal encroachments, where settlements, dwellings or businesses are built directly over or alongside critical infrastructure such as pipelines, valve chambers and reservoirs

The situation is made more complex by social and political sensitivities. Many of the people living on water board servitudes do so out of necessity, driven by housing shortages and unemployment. As a result, eviction or relocation efforts can be highly contentious, requiring coordination with municipalities, law enforcement, and community leaders.

“Rand Water has adopted a collaborative approach, focusing on community engagement, awareness campaigns, and partnerships with local government to prevent new encroachments while addressing existing ones through negotiated solutions. Despite these efforts, informal encroachments continue to expand with urbanisation and population growth across Gauteng. The combination of safety risks, access constraints, illegal water connections, and social pressures continues to make informal encroachments one of Rand Water’s most persistent and complex operational challenges,” adds Monyokolo.Independent regulator

In addition to lobbying for assistance with municipal debt, AWSISA is calling for an independent regulator. An independent regulator would act as a central watchdog, ensuring tariffs are fair, infrastructure is maintained, and all service providers (public and private) meet agreed-upon standards. It would also provide consumers with a place to report grievances and allow service providers to operate in a stable, transparent framework that promotes investment and innovation. Monyokolo cites an example where parliament blocked water boards from implementing a water tariff increase in 2020 due to the Covid epidemic and economics of the country, yet municipalities increased their water tariffs up to 20% during the same year. Water boards and municipalities are not subjected to the same level of regulation.“Water is too important to be managed through ad hoc oversight and political interference. It requires technical consistency, financial sustainability, and public trust. We cannot allow different segments of the water value chain to operate in isolation, each pursuing their own interests, without anyone overseeing the system as a whole. We need a regulator that acts in the interest of both utilities and citizens, ensuring fair and transparent pricing. Let’s regulate for results. Let’s regulate for integrity.”The establishment of an independent regulator was endorsed at the Presidential Indaba, but progress since then has been limited.

Opportunities for water boards

Leaks occur for several reasons — some stem from neglected maintenance of reservoirs, pipelines, valves and meters, while others result from theft and vandalism

Governance and capacity building

The Vaal Dam

AWSISA has signed memoranda of understanding with Swedish Water House, the Finnish Water Forum, and the UN-affiliated IHE Delft Institute in the Netherlands to strengthen skills and research collaboration. Rand Water itself plans to open a dedicated technical college and, eventually, a university specialising in water and sanitation. Looking ahead, AWSISA intends to expand its influence beyond South Africa’s borders. “Rand Water is already Africa’s largest bulk water utility (providing water to 21 million people), yet it has no continental footprint,” says Monyokolo. “Our vision is to export our governance, technical expertise and professional standards to other African markets. South Africa has world-class water management capacity – it’s time we share it.” AWSISA’s upcoming conference, to be held from 9 to 13 November 2025 at Emperors Palace, will bring together government, utilities, and international partners to tackle pressing water and sanitation challenges. The event will also serve as a platform to advance discussions on legislation, SPV partnerships, and practical steps toward achieving SDG 6.

“Our message to delegates is simple,” concludes Monyokolo. “Collaboration is no longer optional. Water boards, municipalities and national government must work together if we are to restore water security, dignity and trust. Water is life – and we must protect it collectively.”