Not many start-up companies are entering the freight forwarding industry in South Africa. *Dave Logan explains why.

While freight forwarding may seem fairly easy, it’s really a complex industry. One doesn’t just launch a freight forwarding business overnight. For a start, you have to register with customs if you’re going to do Customs Broking, which is a natural extension of freight forwarding; you need to sort out deferments with SARS; and you’ve got to put up guarantees, which, in some instances, can equate to 100% of the guarantees on VAT. General compliance with legislation is becoming increasingly difficult and there are a lot more government agencies performing cargo inspections. When the NRCS was a part of SABS, we didn’t experience the container stops that we do now; imports only had to be compliant with SABS standards. The industry understands why the compliance is necessary, but the issue is that it takes a certain amount of time and adds costs to the supply chain. The country’s logistics costs, as a percentage of its GDP, are already high – at around 12.5%. If you provide marine insurance, you need to be either a financial services provider registered with the Financial Services Board (FSB) or become a juristic representative of your insurance broker, who must also be registered with the FSB. If you fail to do this, you can’t provide marine insurance directly. The South African Insurance Association raised this issue with one of our members and we were thinking of changing our standard trading conditions. If you’re not registered with the FSB as a financial service provider or you’re not acting as a juristic representative via your insurance broker’s registration with the FSB, you could be subject to a fine of R10 million, 10 years imprisonment, or both. If someone approaches you and asks that you do their shipments all you can say is: “Do you want marine insurance?” You can’t give advice as you could be held liable – you’ve got to get your broker to do that. You also have to be very specific about the way your contracts are worded. There are a number of pitfalls in that area. Some tenderers demand to know if a freight forwarder is a member of a national association. At SAAFF, we have a code of ethical conduct, to which members must adhere. It’s a way to ensure a standard of service is provided.A topical issue at the moment is the impending Customs Control Act, designed to stamp out illegal trade – one reason why SARS is making use of high-tech container scanners at the points of entry.

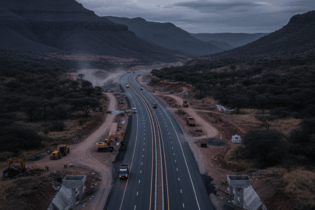

The new R38 million scanner at the Cape Town port will likely be followed by similar systems at Beit Bridge. It is a positive development, as illegal trade is a massive issue in South Africa – with the fiscus losing around R5 billion from illegal cigarettes last year alone. While the original Customs Act was promulgated in 1964 and has been amended over the years, the operative word in the new Act is control – that’s what SARS wants more of. This explains why there are a lot of reporting requirements in the new Act, particularly when it comes to the movement of containers. The Act will impact everyone operating in the supply chain, so companies will need to adhere to the detailed reporting requirements being set out. It is a complex piece of legislation, which SARS has been writing for more than five years now. Being an electronic process, it will need to be adequately policed. Access into and out of the country for goods and people is also being made ever tougher through initiatives like the Border Management Agency (BMA). We’ve already got a number of agencies – Port Health, the National Regulator of Compulsory Specifications, the SAPS Border Police, and the Customs Border Control Unit, which might one-day form part of the BMA. There have also been some proposals on taxing exports but, if that comes in, it will do more damage than anything else. *Dave Logan is CEO of the South African Association of Freight Forwarders.