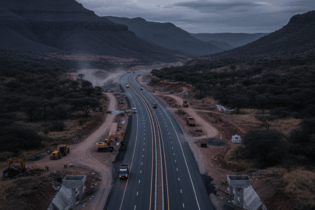

The North-South transport corridor from Durban to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania is arguably Africa’s most important trade route of all writes Tristan Wiggill.

But, while the above statement may hold true, for South African companies, the North-South route is still too heavily skewed in favour of exports. Very simply, not enough containerised cargo is being moved in and out of the country along this route. “Most cargo transported by road to Tanzania is project work related and frequently includes things like engineered goods, mining equipment and chemicals. Most other consumer goods are imported by Tanzania directly from Asia, along long-established shipping routes,” confirms Dune Reddy, owner of Reddy Logistics. Fits and starts There are multiple stop-off points for truckers along the 4 000 km plus road journey from Durban to Dar es Salaam, with drivers typically making use of the rest facilities provided in larger towns and cities for safety, infrastructure and fuel-quality reasons. Reddy says there is a big drive to improve the quality of truck stops, especially in Zambia. Hospitalities aside, the general rule of thumb is that the further north from South Africa one goes, the less developed truck stop facilities become. Diesel quality is also seldom at the level available in South Africa, where 50 ppm diesel is regularly and widely available. Instead, diesel outside South Africa is predominantly of the 500 ppm variety and known to be dirtier than the South African equivalent. Paying for fuel with cash continues to present problems for drivers, who are already highly susceptible to criminal elements. Parking fees have to be paid wherever drivers choose to sleep and, while a level of cashless payments does exist, particularly in Botswana, the fallibility of GSM connectivity in the region and the need to carry cash for border processing means that this vulnerable form of payment cannot be eliminated. Alternatives Given the loads carried and distances travelled, rail offers the obvious alternative to road transport along the corridor. The efficiencies of rail simply outweigh the costs and speed of road haulage. It, therefore, comes as no surprise that governments are looking to move rail-friendly freight from road to rail along corridors like this. The early 2015, the value of rail projects across Africa was estimated at $495 billion; a significant investment in a continent where less than 15% of all freight is carried by rail and where urban centres have only just reached the required numbers to make mass intercity metro transport a viable possibility. However, switching to rail is a complex decision for cargo owners. While existing state-owned entities and other operators are in place, the planning and regulation of the various rail systems differs in vision, content and implementation. Yet, the biggest factor contributing to delays in cross-border rail movement are not related to customs, immigration or other border-related procedures, but instead the lack of coordination among national (monopolistic) rail systems in the region. Specifically, the problems relate to a lack of reciprocal access rights among national operators and a failure to coordinate operational planning. Locomotives from country A may not be allowed to operate on the network in country B because the operator of the network in country B cannot guarantee technical assistance to broken locomotives belonging to another operator. As a result, locomotives often stop at the border and hand over to another operator, leading to long interchange delays. An analysis on the North-South corridor by Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic (AICD) in 2011 indicated that a rail journey of 3 000 km from Kolowezi (DRC, near the Zambian border) to Durban can take up to 38 days to complete, of which 29 days are spent at the border due to delays – resulting in an effective speed of less than 4 km/h. Reducing border-related delays will have a huge impact on the viability of rail for regional traffic. Ports like Mombasa in Kenya and Dar es Salaam in Tanzania can only survive with the development of rail, and ports need rail to survive the current commodity crunch. Existing rail networks in Africa are, generally, in fairly poor condition and require upgrades to infrastructure (both track and signalling), stations and rolling stock as well as road and rail network extensions in order to adequately service passenger and freight demands. Money matters The North-South corridor provides two distinct road routes to Lusaka, Zambia, from South Africa. One goes through Zimbabwe; the other runs through Botswana. The Zimbabwe route is shorter by around 150 km, but is often slower, due to inefficiencies at the infamous Beitbridge border crossing, where delays with documentation frequently last two or more days. A major limiting factor for the corridor is that the sub-Saharan Africa region is beset with notoriously high transport costs compared to other major regions in the world. Population density is relatively low, and a substantial fraction of people reside far from the coast. Ocean navigable rivers, which provide transport to the interior of most other regions, are virtually non-existent and road networks are, on the whole, sparse and poorly maintained. Despite this, 85% of Africa’s internal transportation is still undertaken by road. Around $7 billion is invested in road construction and maintenance in sub-Saharan Africa every year and, while it may sound substantial, China, by contrast, with less than half Africa’s land mass, allocates $45 billion annually to road works, much of it going to extensive highway systems. Given its dependence on road infrastructure, Africa remains poorly served. Good paved roads, over any reasonable distance, remain a scarcity, with additional vehicle maintenance being a costly necessity. Western ways Because the currency used in Zimbabwe is US dollar-based, fuel costs are higher on this route. Bribery and corruption by customs authorities is also more prevalent. Zimbabwe is the more mountainous route than the Botswana alternative, with heavy commercial vehicles under more mechanical strain, to the detriment of travelling speed and fuel consumption. At around eight to ten hours, the South Africa/Botswana Groblersbrug border post is quicker to process documentation than the Beitbridge alternative. Botswana roads are flatter than Zimbabwe’s and its fuel is cheaper – even cheaper than South Africa’s – despite the fact that it imports all of its fuel from its southernmost neighbour. Delays almost always occur at Kazungula leaving Botswana for Zambia, as there is no bridge and, so, road transporters have to wait for a ferry to get across. Transporters often choose to overnight in Lusaka once in Zambia and then drive 1 000-odd kilometres to Tunduma, the border separating Zambia and Tanzania. Paperwork in Tanzania is handled in Dar es Salaam and not at the border post, as the country uses a single, centralised point for documentation. Documents are then sent back down to the Tanzanian border, which takes additional time (frequently between four and seven days). Like Zimbabwe, corruption in Tanzania is commonplace, with drivers regularly involved.Identified by their number plates, South African vehicles are frequently targeted by criminals. The thinking goes that South African transport and logistics companies carry more money onboard than their SADC and East African counterparts.

A considerable frustration for South African transport and logistics companies is that transported loads are only carried the one way, with empty trucks returning to South Africa. It is difficult to return with a full load as South Africa imports very little from East Africa; volumes which could be sent by air freight. Special cross-border permits also have to be issued, which are only valid for a single country of origin and single country of destination. Usual suspects The implementation of One-Stop Border Posts (OSBP’s) is an attempt to address crippling border congestion problems on the route. By allowing each of two existing border posts to deal with traffic flowing in one direction only, it is possible to eliminate the ‘no man’s land’ between border posts. Unfortunately, the development of OSBP’s is minimal on the continent, with only Chirundu and Uganda’s Busia, Mirama Hills and Mutukula entry points functioning examples. A lot of corruption occurs at border posts and, once congestion begins to be eliminated, and the possibility of corruption reduced, objections begin to surface. Things don’t seem to be getting better in Zimbabwe; with the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority’s (Zimra) roll-out of customs updates last year deemed “an absolute shambles” by the South African Association of Freight Forwarders (Saaff). Zimra had to withdraw the updates and reintroduce them after a lot of work had been done, but not before several weeks of delays. The Zimra manually-operated release desk, as a whole, is still a major headache for the Saaff and, while the Zimbabwe Freight Forwarder’s Association has liaised closely with Zimra, it’s still seen as a hive of corruption. From the South African side, the main issue pertains to gate processes. There are two fairly separate gate processes, with the service managers system quite a lot older than the inter-front system. All too often though, glitches occur with the two systems failing to ‘speak’ to each other. This may well have monetary implications for clearing and forwarding agents, once the new Customs Control Act is promulgated and rolled out. Practically speaking, the big issue facing the North-South corridor is the cost of intra-Africa trade. The mooted Free Trade Agreement is an exciting development, even though much cynicism exists in business circles about it. While seemingly insignificant on the surface, the 66 km, four-lane Pedicle Road linking Zambia’s Luapula Province to the copper belt, through the DRC, will assist business in the region tremendously. In fact, economic benefit has already been seen, but, unless it becomes a functioning OSBP, and unless the Congolese and Zambians work together, time is still going to be wasted at the border. Modernisation drive When it comes to remedying border delays, priority needs to be given to the entire corridor, not to sections of the corridor. Challenges are not just operational – too few performance monitoring tools are available as well. That being said, efforts are underway to address the continent’s border problems. The South African Revenue Service (SARS), for example, plays an important role in intra-Africa trade facilitation. In 2000, it started to aggressively pursue Electronic Data Interchange (EDI), which laid the foundation for its customs modernisation drive. “Border security became more important in the wake of 9/11,” explains Beyers Theron, executive: Customs Modernisation Strategy and Design at SARS. “During that time, we started to get automated risk engines; we started to work with other government agencies to exchange data, specifically with the South African Reserve Bank, the Dti and ITAC. “SARS started to see itself less as a gateway to trade facilitation and more as a player in the supply chain and it followed a risk management approach. The current programme of modernisation looks at integrated risk – that is, not just the customs portfolio.” “We started to implement a lot of automation in our systems. As a world-first, we introduced a hand-held inspection reporting tool, on which we can, from a border post, engage with a customs centre, follow instructions and perform decision-making tasks. We’ve become more flexible to how things work in the customs world. Automation has occurred and a lot of paper has been taken out of the declaration process.” “If traders are compliant when reaching the border, we can process them through within a few minutes. If we are transparent and if our requirements are predictable, then it makes it far easier for trade to move through a border post,” he says. Disruptive innovation Dar es Salaam cargo volumes are growing at 10% per annum, with intra-regional trade growing quickly and, therefore, providing a wealth of opportunities for transport and logistics service providers. But, the cost of transporting inbound and outbound containers is still prohibitively high; it costs almost $5 000 to transport a single container from the Dar port to Rwanda, for example. A lot of work is being done on the northern corridor out of Mombasa in Kenya, with noteworthy investment received. Numerous donor projects have been completed and the private sector continues to get involved. “We need to think about intra-regional trade within the East African Community (EAC), which has some of the best dynamics on the continent in terms of the countries trading with each other,” says Isaac Njoroge, fund manager at the Logistics Innovations for Trade (LIFT) Fund. “The LIFT Fund is looking for disruptive innovation; a solution that is based in Africa for Africans, which no-one has thought about. We are looking at things like freight exchanges, and the use of ICT that allows that to happen. We need to develop things like pallet networks to allow small players to distribute cargo in sizes that make sense to them. We should use ICT in vehicle management, where we try to get virtual networks of SMME hauliers and transporters to work together and look at the different models that emerge from that. “We could, at a higher level, look at paperless systems to handle road tax, insurance and certificates of roadworthiness, which could reduce burdens and increase transparency and lift revenue collections for authorities. We’ve been talking about electronic Bills of Lading for a long time, which haven’t changed much from the 18th century. Electronic container locks could also be used, and are controlled by mobile phones, which allow containers to be traced. These are the types of technology disruptions we need,” he says.