South Africa has a long and prestigious history of wastewater treatment process modelling that is internationally recognised. Sadly, there is a slow, minimal uptake of this research and work by our own municipalities.

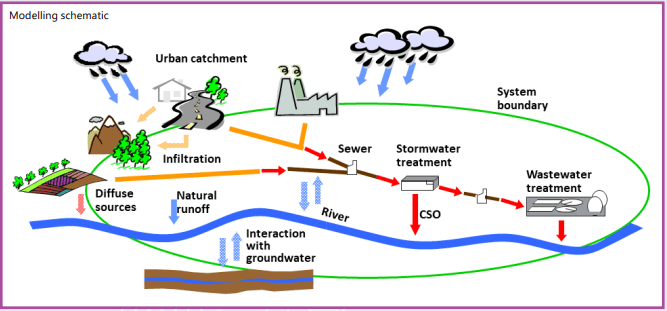

By: Kirsten Kelly Large, better-resourced municipalities and water services authorities – like the City of Cape Town, eThekwini and the Ekurhuleni Water Care Company – have some capability to implement process modelling,” says Barbara Brouckaert, research fellow at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) WASH R&D Centre. However, academics and consultants take up most of the work. “In theory, some municipalities have some very capable people to do modelling, but these people also have a host of other responsibilities and there are time constraints. The time and data needed to set up a working model are often underestimated. Effective modellers have a specific mindset and need space to work intensely for long periods without being distracted by other responsibilities. It is very difficult to persuade municipalities to invest in that resource,” explains Chris Brouckaert, senior research fellow at the WASH R&D Centre. Advantages Wastewater process modelling can provide a host of benefits in terms of the management and planning of wastewater treatment works (WWTWs), such as: • creating a better understanding of how to improve the design and operation of WWTWs • evaluating the benefits, impacts, and feasibility of planned upgrades • accurately estimating potential chemical/energy savings • risk analysis • predicting performance under various operating conditions and control strategies, including future changes in the quantity and quality of water/wastewater • analysing system dynamics, e.g. the impact that a sewer system may have on the WWTW • prioritising interventions that will have the greatest system-wide impact Local context “Instead of trying to pursue ultimate sophistication, we have adapted process modelling to suit local conditions in the wastewater sector, where there is poor data and information availability, and unreliable infrastructure,” says Chris. Barbara elaborates that the process modelling of WWTWs requires a lot of data, and much of that data is not routinely available (like biodegradability). “Furthermore, the available data is frequently incomplete and inconsistent, because most of it is seldom actually reviewed or used for anything. Collecting data and getting it into a usable form is usually the biggest part of the modelling effort.” Conducting measurement campaigns for additional data is expensive and time-consuming, and it is difficult to get representative values due to the highly variable nature of domestic wastewater. The UKZN modelling group and Professor David Ikumi’s Water Research Group at the University of Cape Town (UCT) make up the South African Development Centre for WEST, the Danish Hydraulic Institute’s software for advanced wastewater systems modelling. However, both groups also focus on developing models and modelling tools that are adapted for local conditions. For example, UCT has developed several steady-state modelling tools in Excel, including a tool for estimating the capacity of an existing WWTW.“The design capacity – the number of megalitres per day of wastewater a plant can treat – is always a focus point for local government. However, it has become important to determine how many megalitres per day a plant can treat with ageing infrastructure and failing equipment. We need to calculate the actual functional capacity of WWTWs,” explains Chris.

The term ‘functional capacity was coined by a process engineer in eThekwini Municipality’s Water and Sanitation Department (EWS). It refers to the megalitres per day a WWTW can process with its existing equipment and operational arrangements. There are frequent queries regarding the capacity of WWTWs to process wastewater from prospective housing developments or businesses. While the design capacity may indicate that a WWTW could accommodate new development, the functional capacity often presents a different picture. “This is where modelling WWTWs can provide value – it can scientifically demonstrate the functional capacity of a WWTW and provide an analysis of what needs to be done (in terms of upgrades, replacement of equipment, operational changes, additional resources) at the WWTW in order to accommodate more wastewater,” states Chris. In addition to improving the generation and collection of accurate data, as well as employing full-time modellers, Barbara adds that there needs to be a dialogue between the model, theory, concept and the reality in the WWTW with its operational staff. “Typically, the operational staff generate the data and they have to understand why that data is important. Additionally, clear modelling objectives that align with the priorities of the municipality or WWTW management will determine the level of detail required, and where the modelling efforts need to be focused.”

at the UKZN WASH R&D Centre

UKZN WASH R&D Centre