Public water supply is the responsibility of utilities and government, but public water connected to a building is the building owner’s responsibility.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) water within buildings is assumed to be safe because it is supplied publicly, however, this ignores the risks of contamination and waterborne pathogens that can occur within these systems. This problem is ever-present, but it was exacerbated during the pandemic. Buildings that were once busy closed during lockdowns which led to pathogens like Legionella growing in these systems. According to Ayesha Laher, a registered professional scientist and director of AHL Water, “This highlighted the existing problem, quite a serious problem, and suddenly people realised that there is an issue of water quality within buildings.”

This problem is compacted by the fact that regulatory authorities provide oversight of public water supplies, but do not have authority over the thousands of privately owned buildings in South Africa. Furthermore, these water systems are often maintained by general staff without the necessary skills or training required to effectively maintain safe water quality. The assumption that the public water is safe can also be faulty, as there has been a serious deterioration in water quality from municipalities, as well as intermittent supply.

Ayesha Laher, director of AHL Water

External Problems

The scope of the problem extends to both internal and external factors that determine water quality within a building. Ayesha identifies three key external problems that buildings are faced with:

Municipal supply is not safe as per the 2023 Blue Drop Report

- 51% of water supply systems have unsafe water.

- 45% of systems do not comply with acute health determinants.

- Only 29% comply with monitoring requirements- there is an insufficient number of samples and determinants as per SANS 241.

Contamination in the reticulation network

- Ageing infrastructure

- Loss of pressure/Intermittent supply

- Long residence time

- Failing reservoirs

- Illegal connections

- Theft and vandalism

Lack of reliable supply of water

- Lack /Insufficient supply

- Insufficient pressure

- Ageing infrastructure, theft and vandalism, illegal connections, lack of maintenance

- Lack of political will.

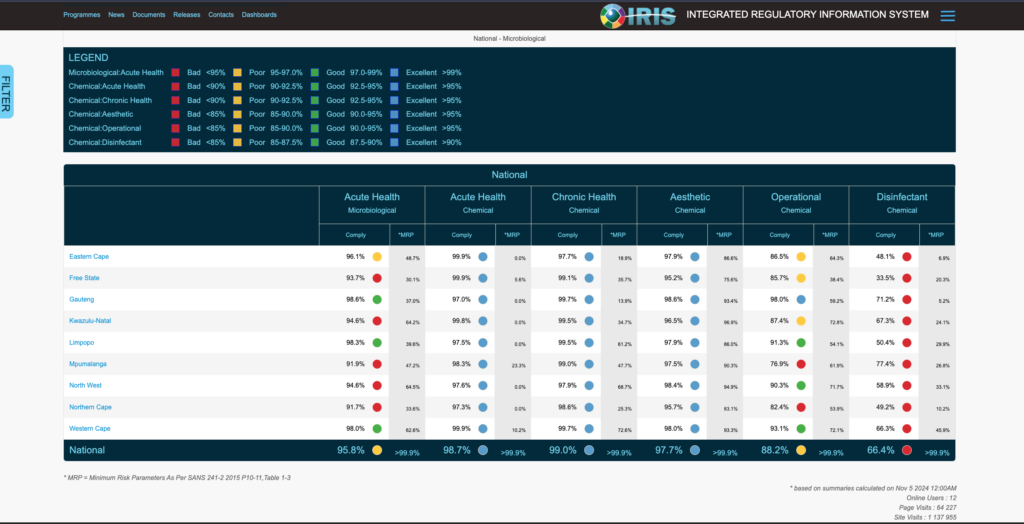

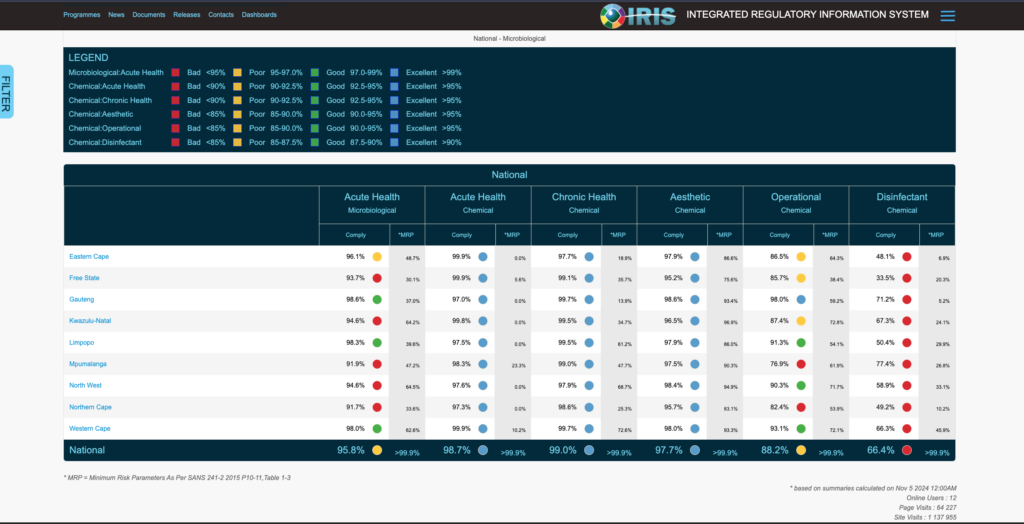

“These problems are connected, and while some are noticeable such as insufficient supply, others such as long residence are less visible but equally problematic,” adds Ayesha. She advocates that the public should be informed about the state of their water, and says, “The Regulatory Information System of the Department of Water and Sanitation is set up to monitor the water quality of municipalities. Every month municipalities submit data, and you can get a good overview of the water quality in your area, or you can see how big the problem is.” This monitoring site shows that even before water enters a private building there are problems with it, and thus the risk is passed from the public supply to the building owner.

“If you spend some time on IRIS, you will spot some worrying trends. A low-value MRP tells you there are insufficient sample points. Anything below 99% compliance means that the water quality has issues. I would advise not to drink water from municipalities that have less than 96% compliance with microbiological standards,” says Ayesha.

IRIS allows public access to the water quality in South Africa.

Internal problems

Once the water is in the building, there are internal problems to deal with. Ayesha points to seven main problem areas:

Point of entry

- Incoming water contamination

- Loss of supply

- Failure of back-flow prevention device

Solar Preheat systems

- Water stored at below 60°C promotes Legionella growth

- Booster failure

- Heater failure or under-capacity

- Build-up of sludge in the tank

Hot Water Systems

- Thermal stratification

- Storage temperature too low (below 60 °C), potential for Legionella growth

- Risk of scalding

Cold Water Systems

- Water stagnation

- Contamination of storage tank

- Build-up of sludge in the tank

- Water temperature >20 °C

Outlets

- Poorly maintained outlets

- Unused outlets

- Flow restrictors

- Aerators

- Outlets that hold water after use (e.g., shower heads or hoses)

Treatment systems

- Dosing failure

- Insufficient dosing

- Running out of disinfectant

Pipework/Plumbing

- Dead legs and capped pipes

- Cross connections between potable and non-potable pipes

- Deterioration of insulation (lagging) around pipes

- TMV malfunction or inadequate maintenance

- Long distances between TMV or tempering valves and outlets

- Corrosion due to deterioration of materials

- Pipe leaks due to age

- Heating of cold water in pipes (>20 °C)

- Low flow in recirculating loops

- Lack of accessibility for repairs and maintenance

- Incorrect design and installation of plumbing systems by unqualified plumbers.

- Lack of accredited plumbing materials

Legislative overview

The external and internal problems are now determined, and the answer to ‘who is responsible’ should be found in the legislation. This begins with the National Water Act which states that “the Minister is the trustee presiding over our water sources. They must ensure that water resources are protected, used, developed, conserved, managed, and controlled. The Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) is responsible for oversight and regulations.” Within the National Water Act is the Water Services Act and this deals with potable water. According to this act, local government is responsible for the provision of water services- providing water to water users. Local governments are then subject to standards set by DWS. Municipalities must also monitor their water for compliance. This data then gets reported in the Blue and Green Drop Reports. These water services authorities (WSAs) are subject to norms and standards as per SANS 241, noting that the responsibility of the WSAs stops at the point of entry to private property. This means that SAN 241 does not have legislative requirements over water within a building. Then there is Water use efficiency: Sections 9(1) and 73(1)(j) of NWA that state the “Regulations relating to compulsory national standards and measures to conserve water,” where WSAs must take steps to reduce the quantity of their water.

Ayesha says, “Once the water enters a private dwelling, the onus is on the property owner to effectively utilise the water, ensure there is no additional contamination from external sources, and safely dispose of any wastewater that cannot be disposed into the municipal system.”

Governing the building is a separate set of legislative guidelines found in the National Building Regulations and Building Standards Act (Act No. 103 of 1977). Ayesha explains “The legislation that talks to buildings highlights the health and safety requirements for these buildings, but importantly building control officers do not have jurisdiction over internal water networks. Also, SANS 10252: which speaks to Internal water networks does not form part of the legislative requirements, rather they are voluntary, not enforced and are used by engineers and plumbers to design water services in buildings.”

South Africa legislative requirements leave gaps for risks to creep through

Legislative gaps

Between these legislative requirements, there are gaps that can lead to confusion on who is responsible for what, and what the necessary steps to ensure water quality are.

Water Use Efficiency: NBR and BS Act

- Water use efficiency is not currently addressed under the NBR.

- A voluntary SANS 3088:2019: Water efficiency in the building has been developed, and will be incorporated into SANS 10400

- Building Control Officers will only ensure compliance of the fixtures/fittings during construction and are not responsible after the construction.

Water Quality: NBR & BS Act

- Water risks are treated as ‘minimal’

- It is assumed that municipal drinking water is safe. It is assumed that water quality and supply are covered by another department such as DWS.

- Non-technical aspects related to water quality and alternative water sources are not included in the proposed new water regulations and should be included in local bylaws as WSAs have the required skills (water quality) to enforce these regulations.

Legionella: SANS 893-1/2

- This is a voluntary standard as per the Occupational Health and Safety Act, No 85:1993

- The control of Legionella through temperature control at 60°C or higher must be measured against the risk of scalding.

- There is no compulsory standard for installation of mixers.

Bylaws and entities

With the legislation having gaps, there are local bylaws that differ from one municipality to the next to aid in water quality management. Local bylaws set the legal and voluntary requirements within a municipality’s jurisdiction, there are ‘model bylaws’ developed by the DWS but no enforcement to take these up. Local bylaws are also rarely updated and poorly enforced.

The Department of Health deploys environmental health practitioners to inspect select reservoirs, such as ones that supply universities and hospitals, but there is no communication with municipal water services.

There is also the Plumbing Industry Regulation Board which is a non-statutory board for professional plumbers. This board advocates for the installations to be done by professional plumbers who comply with all legislative standards including voluntary ones. Some municipalities have mandated the use of professionally registered plumbers, while others have not.

Solutions to the problem

The problem of water quality in buildings is wide, from confusing standards to the lack of proper enforcement. However, there are solutions. Ayesha says, “Focusing on the problem to truly understand the depth of it, is important, but without solutions, it can feel futile, and there are solutions.”

Ayesha identifies three main ways to address the problem:

Water quality assessment: This entails using the IRIS program to assess the supply of water coming into the building. From this information, it is possible to do a ‘case by case’ risk assessment with preferred solutions. For example, if the water coming into a building is found to have bad acute microbiological compliance, then the identified risk is that the water poses a risk to the acute health of those who drink it. From this scenario, the recommended action will be to “Provide an alternative supply until the microbiological contaminant is removed, as well as install a disinfection unit at the facility to reduce pathogens in the water supply.” This recommendation is then broken down into “immediate,” “one to 3 months” and “monthly” actions. An ‘immediate’ action would be to use an ILab test kit and check for E. coli in water, and to stop the supply if found. A medium-term action would be to install a disinfection system at the facility. A monthly, or routine action would then be to conduct monthly testing .

The iLab test kit is a trusted way to test water quality.

There are also several guidelines you must comply with, such as the NBR. If you are going to build a treatment plant you must comply with the NBR, Environmental Impact Assessments, as well as local by-laws. Above that, if you are extracting above a certain amount you must apply for a water use license which starts at about R50000. Ayesha points out that, “It is especially important to consult local laws, for instance, you cannot use groundwater water for commercial purposes in Johannesburg and Ekurhuleni. If you are a commercial building in those areas, you must get approval from the council before you are allowed to use alternative supplies such as groundwater.” If you are pursuing boreholes as supply, then there are laws you must comply with. The borehole must be dug by someone who understands these practices, and the borehole must not be over-extracted where this could lead to sinkholes.

The design of a water treatment plant will be highly dependent on what the specific situation entails. “There is no use in having a very complex, reverse osmosis system if your water does not require that kind of treatment,” says Ayesha, and adds, “Plant capability is also not restricted to design.” Beyond these requirements is that your plant must comply with the Blue and Green Drop standards. If this is overwhelming, this is why scientists like Ayesha are available- to give accurate information and suggestions

Risk Management approaches: Ayesha says “Building owners can be proactive in managing their risk and conduct a risk management assessment to develop a water safety plan.” This involves the four-step process of identifying risks, assessing the risk controlling the risk, and evaluating the control method. Notably this is the approach that the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends, and having a water plan that is proactive to risk management can prevent water related risks in buildings.