African cities are growing at an incredible pace. With this growth comes a mix of opportunity and challenge. How do we build cities that are not only smart but also fair, inclusive and resilient?

A smart city uses digital tools such as sensors, data networks and connected devices to run services more efficiently and respond to problems in real time. From traffic and electricity to public safety and waste removal, smart technologies aim to make life smoother, greener and more connected. Ideally, they also help governments listen to and serve citizens better. But without community input, “smart” can end up ignoring the people it’s meant to help. That’s why a different approach is gaining ground. One that starts not with tech companies or city officials, but with the residents themselves. I’ve been exploring what this looks like in practice, in collaboration with Terence Fenn from the University of Johannesburg. We invited a group of Johannesburg residents to imagine their own future neighbourhoods, and how technology could support those changes. Our research shows that when residents help shape the vision for a smart city, the outcomes are more relevant, inclusive and trusted.Rethinking smart cities

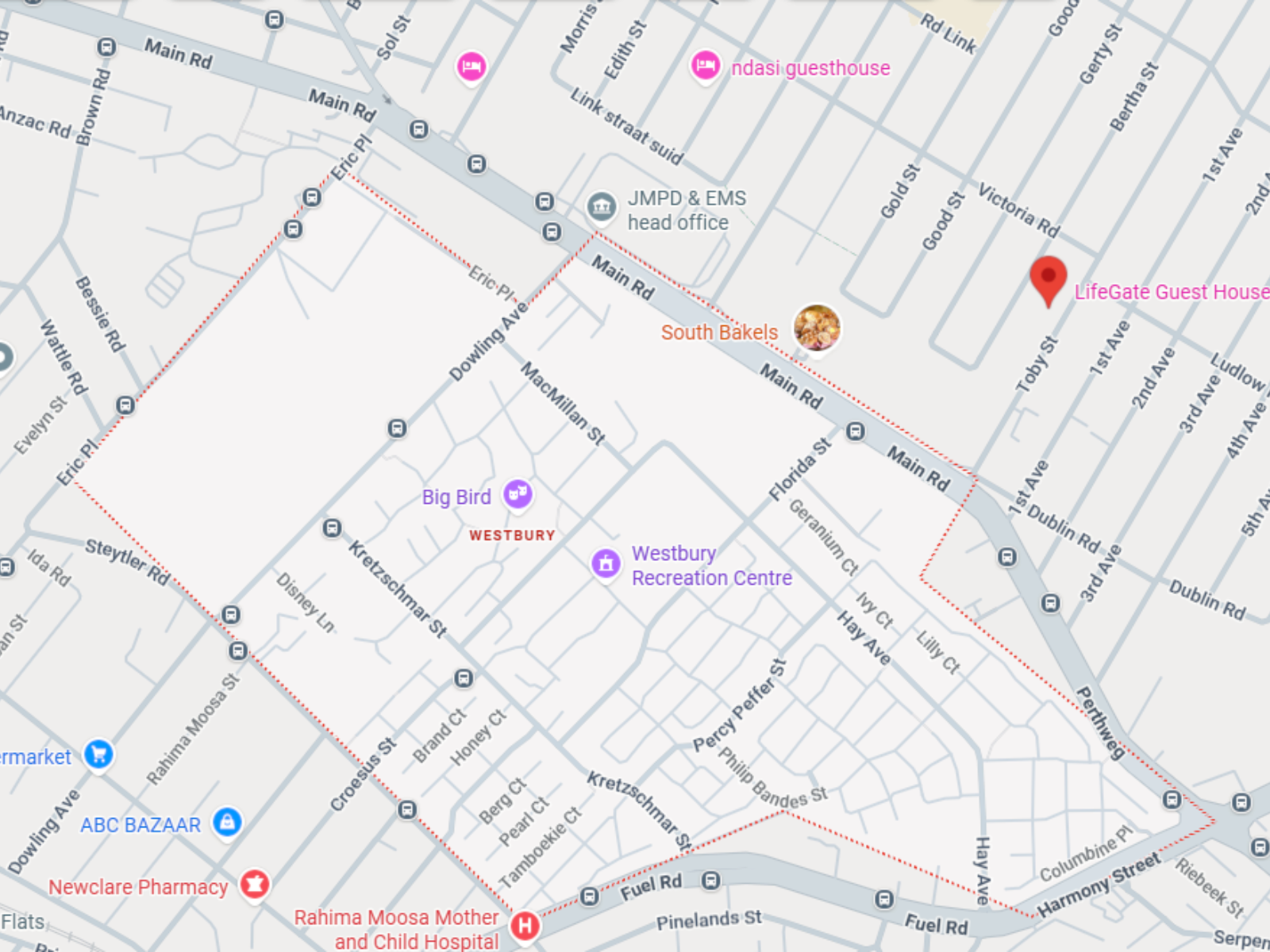

Westbury area, Johannesburg city

Safety was a top concern. Residents imagined smart surveillance systems that could help reduce crime, but they were clear: these systems needed to be locally controlled. Cameras and sensors were fine, as long as they were managed within the community by people they trusted, not some distant authority. The goal was safer streets, not more control from afar.

Safety is a deeply rooted concern in Westbury, where residents live with the daily reality of gang violence, drug-related crime and strained relations with law enforcement. Trust in official structures is eroded. The desire for smart safety technologies is not about surveillance but about reclaiming a sense of control and protection. Energy came up constantly. Power cuts are a regular part of life in Westbury. People wanted solar panels, not as a green luxury but as basic infrastructure. They imagined solar hubs that powered homes, schools and local businesses even during blackouts. Sustainability wasn’t an abstract goal; it was about self-sufficiency and dignity. Technology also opened the door to cultural expression. Residents dreamed up tools that could make their stories visible, literally. One idea was using augmented reality, a technology that adds digital images or information to the real world through a phone or tablet, to overlay neighbourhood landmarks with local history, art and personal memories. It’s tech not as a spectacle, but as a way to connect past and future. And then there were ideas about skills and education: digital centres where young people could learn to code, produce music or connect globally. These were spaces to build the future, not just survive the present. People imagined smart tools that could showcase local art, amplify community voices, or support small businesses. In short, the technology imagined in Westbury wasn’t about creating a futuristic cityscape. It was about building tools that reflect the community’s values: safety, creativity, shared power and resilience.