When record-breaking rains swept through the coastal city of Durban in South Africa in April 2022, the resulting floods destroyed roads, bridges and homes. Durban’s low-lying, poor neighbourhoods were hardest hit, with residents losing their homes and their lives.

The scene would have felt familiar to residents of many other of Africa’s fast-growing cities. Some, including Lagos, Cairo, Cape Town and Durban, have already faced the need to adapt to a changing climate and its intensifying hazards such as floods, droughts or intense heat. Cities need new ways to adapt to climate change. The current system of social, economic and political structures that cities are based on is built on a market-led capitalist model and globalisation. This model has caused cities to grow in ways that make economically and socially disadvantaged and underserved people more vulnerable to climate hazards. For instance, many poor residents can only afford to build flimsy homes or live in flood-prone areas near rivers. When climate change brings bigger floods, it’s those neighbourhoods that get hit hardest. The usual response of most city administrations is to make relatively small changes, like strengthening flood barriers or improving drainage. These aim to reduce climate risks while keeping the underlying social, economic and political system in place. This approach is called incremental adaptation. But the effects of climate disasters show this approach isn’t working. The solution is transformative adaptation. This is about pushing for bold, wide-ranging changes that tackle the root causes of vulnerability and build a society that’s more equitable, just, sustainable, and inclusive for everyone. How to do this in practice is still being explored. Together with our co-authors, Rudo Mamombe and Patrick Martell, we research climate risks and adaptation planning in cities. We set out to understand how Durban, South Africa and Harare, Zimbabwe – cities that face many spatial and economic inequalities – could achieve transformative adaptation in practice. The research homed in on local water-related climate risks: erratic rainfall, floods and droughts. We formed learning labs – groups where we could discuss complex issues with local municipalities, non-governmental organisations, civil society organisations and research organisations. Here, we distilled six principles for transformative adaptation. We then tested those principles against five real-world, water-related projects. The six principles offer a practical guide for city managers, community organisers and donors to pursue the kind of climate adaptation that advances social, economic, and political justice.Six ingredients for deeper change

These are the six principles we identified:- Fundamental changes in thinking and doing, which must be sustainable: radical changes to the existing norms, values and ways of doing things.

- Inclusivity: multiple and diverse groups who are all given real influence over the decisions to be made and carried out.

- Challenges to power imbalances: social justice results from disrupting existing power structures.

- Demonstrability: tangible, visible benefits.

- Responsiveness and flexibility: the agility to respond and change as local priorities, conditions and lessons emerge.

- Holistic, complex systems thinking: recognising that many of the forces driving global change, climate risk, and vulnerability are connected. These links cross sectors, places, timeframes and levels of decision-making.

Where we tested these principles

Durban’s Sihlanzimvelo Stream Cleaning Programme, run by the municipality, employs co-operatives of local residents to clear invasive plants and rubbish from almost 300km of streams.

eThekwini Municipality’s Sihlanzimvelo Stream Cleaning Programme. eThekwini Municipality

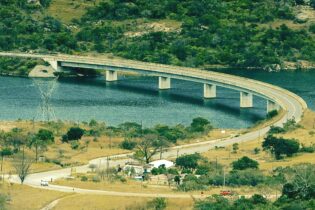

A Harare wetland. HelloRF ZcoolShutterstock

The team who worked on the Palmiet river project. Courtesy GroundTruth