Reon Pienaar, a professional civil engineer at the specialist waste management consulting company JPCE (Pty) Ltd

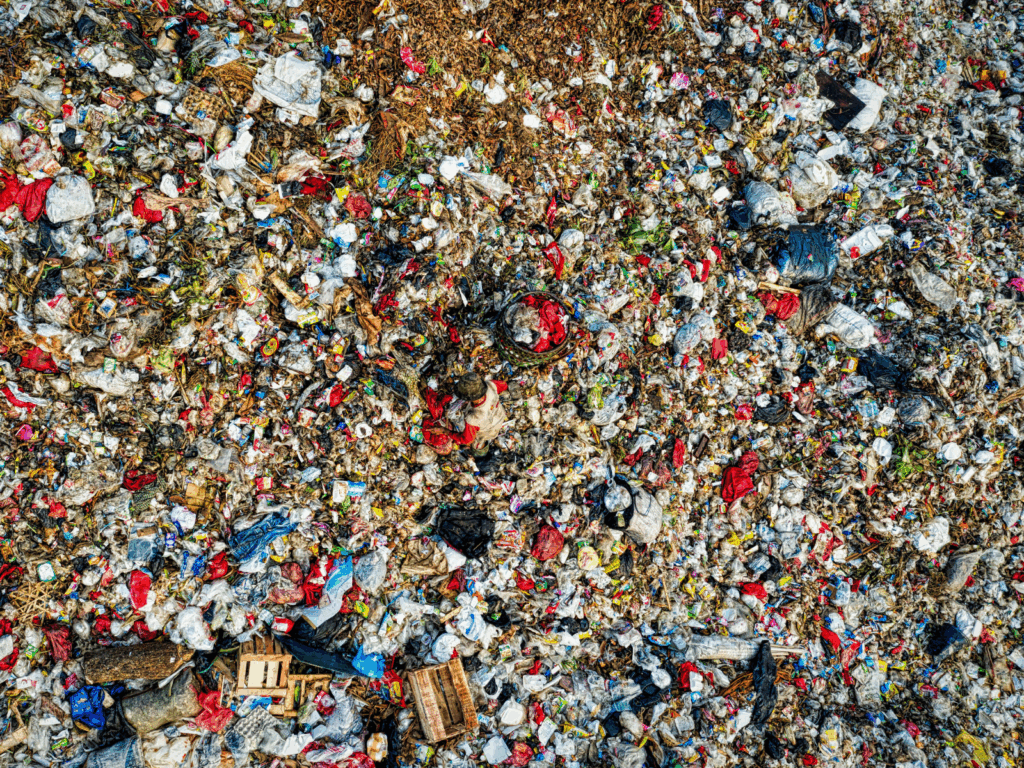

The landfills in South Africa are filling up, and the airspace, while crucial, is limited.While diversion, separation at source, and recycling have received a big push as of late, the data suggest that as much as 80% to 90% of South Africa’s waste is still heading for landfill sites. Pienaar adds, “While it is important to aim high and look at countries with a high landfill diversion rate, we need to look at and understand our context in South Africa. Many rural and informal spaces do not even receive a basic waste collection service, and most collected waste is often taken directly to landfills. It is also important to note that even with a high recycling and diversion rate some waste remain unrecoverable and landfills will still need to exist to accommodate this.”

The airspace crisis means that landfills will have to be operated more efficiently if they are to continue receiving waste

Engineering from the Ground Up

The issue becomes ‘how does South Africa extend the life of its current landfills’ in order to accommodate waste, and continue basic waste removal? Extending landfill life begins even before the landfill is operational. From the design stage, engineers must anticipate how the site will behave over decades. This involves a complex interplay of geotechnical, hydrological, social, economic, and structural considerations.“If you don’t design a landfill properly from the start, you immediately shorten its sustainable life,” Pienaar emphasises.“The slopes must be engineered to remain stable as waste accumulates. Your drainage systems must be designed to handle both stormwater and leachate, and your lining system must be designed to protect the underlying groundwater. If any one of these elements are compromised, the whole sustainable lifespan of the facility is affected.” Pienaar adds, “Waste management is still a relatively new field of engineering in South Africa, only really starting to gain importance in the 1980s. Dumps, as opposed to engineered landfills, were the dominant way of handling waste and these have a horrid impact on the environment. Comparing them to what we have today, in engineered landfills, is night and day. South Africa is always improving in the management of our waste, and most importantly we have good and strong regulations to assist us.” The life span of a landfill site is dependent on the license conditions issued for each facility. Stormwater is a particular challenge in South Africa’s variable climate, where heavy downpours can overwhelm poorly designed systems. Pienaar notes: “To aid in the optimisation of sustainable landfill life, landfills need to be designed and operated to ensure separation of clean and dirty water. Engineered stormwater channels need to keep clean stormwater from entering the waste body end engineered drainage systems need to manage the rainwater within the landfill.” Modern engineered landfills include the use of geosynthetic materials in the liner design, some of which act as a barrier between the underlying soil and the waste, preventing leachate from contaminating groundwater resources. Other geosynthetics assists with drainage of leachate which is essential to keep the landfill efficient.” Equally important is compaction. The density of waste, achieved through the right compaction methods and machinery, directly translates into extended airspace. “The difference between poor compaction and optimal compaction is measured in years,” says Pienaar. “You can gain years of additional life in the landfill just by ensuring proper compaction techniques are consistently applied.”

The complex engineering of modern landfills means that these sites are built to perform as sustainably as possible

Operations: Daily decisions, long-term impacts

Even the best-designed landfill can fail prematurely and become a risk for pollution if operations are weak. Pienaar highlights the role of daily cover, cell management, and strict operational discipline in maximising lifespan.“Every day, operators are making decisions that affect the long-term viability of the site,” he says. “If cover material is not applied sufficiently or done inconsistently, you can end up with odours, vermin, and fire risk as well as pollution from wind-blown litter. If you allow trucks to tip waste randomly, instead of managing a controlled cell, you can lose compaction efficiency and airspace. These small decisions add up over the years.”

He stresses that landfill life extension is not simply about stretching the available airspace, but also about ensuring compliance and safety. “We should not be extending lifespan for the sake of it. We need to be extending landfill lifespan in a way that protects the environment, prevents contamination, and keeps the landfill aligned with regulatory standards.” In this sense, compliance with the National Environmental Management: Waste Act (Act 59 of 2008) becomes more than just a box-ticking exercise. It becomes a driver of innovation. “South Africa’s regulations are very clear on landfill licensing, lining, monitoring, and rehabilitation,” Pienaar explains. “That framework pushes us as engineers to find smarter ways to design and plan. Compliance is what forces us to innovate.” No discussion of landfill lifespan can ignore the role of waste diversion. While engineering and operations can squeeze more years out of a site, the ultimate solution is to reduce what goes into the landfill in the first place.

Installation of geosynthetic materials as part of an engineered landfill liner, a key piece of tech that helps prevents environmental damage

“Separation at source, material recovery facilities, composting of organics, crushing and beneficiating builder’s rubble, these are all essential tools for reducing the volumes that reach landfill.”Pienaar points out that organic waste is particularly problematic. “Organic waste breaks down and generates methane, which is both a greenhouse gas and a fire risk if not responsibly managed. By diverting organics, we not only extend landfill life but also reduce emissions and safety risks.” There is an entire industry dedicated to managing organic waste, using it for a range of technologies from composting to Anaerobic Digestion, which is much better than ending up in landfill sites where it can become a problem. Recycling rates remain a challenge in South Africa, with only a fraction of potentially recyclable materials currently being recovered. For Pienaar, this represents both a challenge and an opportunity. “Every tonne of recyclables we recover is a tonne less waste into the landfill and directly results in airspace saved. That is why we see recycling not only as an environmental imperative, but as an engineering strategy for landfill life extension.” South Africa’s new extended producer responsibility laws (EPRs) have taken effect, and while optimistic Pienaar says, “It’s too early to tell the full scope of impact, but it’s promising and a very important part of managing the waste lifecycle to minimize waste to landfill.”

Technology and the future of landfills

As the waste sector modernises, technology is playing an increasing role in extending landfill lifespan. Data-driven monitoring systems allow for real-time tracking of compaction density, leachate levels, and gas emissions. Gas-to-energy projects convert methane into a usable energy source while reducing environmental risks. Pienaar says. “The landfill itself has very little in the way of tech on site, but the correct compacting techniques and equipment, measuring and monitoring tools, and on-site recovery all aid in extending the lifespan of a landfill.” For Pienaar, the technological advancement is the way engineers design the landfill to make it as efficient as possible in protecting the surrounding environment. He believes that a cultural shift is also needed. “We must stop thinking about landfills as the only option. They are part of a broader, integrated system that includes recycling, treatment, and energy recovery. The landfill of the future is not just a hole in the ground; it is an engineered facility that sits within a circular economy.”

Lengthening the life of a landfill begins with diverting waste from the landfill